A NEW GOTHIC

In a panel painting by Hieronymous Bosch, John of Patmos sits in the folds of a baby pink vestment clutching a quill held above a book he is in the process of writing. Rendered in Bosch’s signature surrealist and symbolic style, a blue angel hovers behind him on a hillock, whilst at either side of his feet stand a small bird and equally small monstrous animal-human hybrid. John’s eyes are fixed on a vision in the painting’s top-right corner, which seems to keep him in an inspired trance as he writes. The painting was part of a large altarpiece for St John’s Gothic Cathedral in ’s-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands.

Patmos is the place where John was exiled and wrote Revelations, the last book of the Bible which collects a series of prophetic visions in the afterlife. This is a highly enigmatic and symbolic book, with vivid, terrifying visions of an apocalyptic future. The etymology of the term ‘apocalypse’ is derived from the Greek apokalyptein, which alludes to acts of uncovering, disclosing and revealing. The hallucinations and visions which John writes of, serve to forewarn and speculate on what lies ahead. They are considered to have been divinely inspired, laying bare messages from the creator and unveiling imminent happenings on this earth. Monsters, creatures and beasts are as abundant in the visions of John, as they are in works by Bosch. They seem to immerse the human into fantasy and open up for debate on issues of morality, religiousness and human consciousness. They use the duality of awe and fear to speculate on the role of the human in the natural world, and they take the biblical as a location for human introspection.

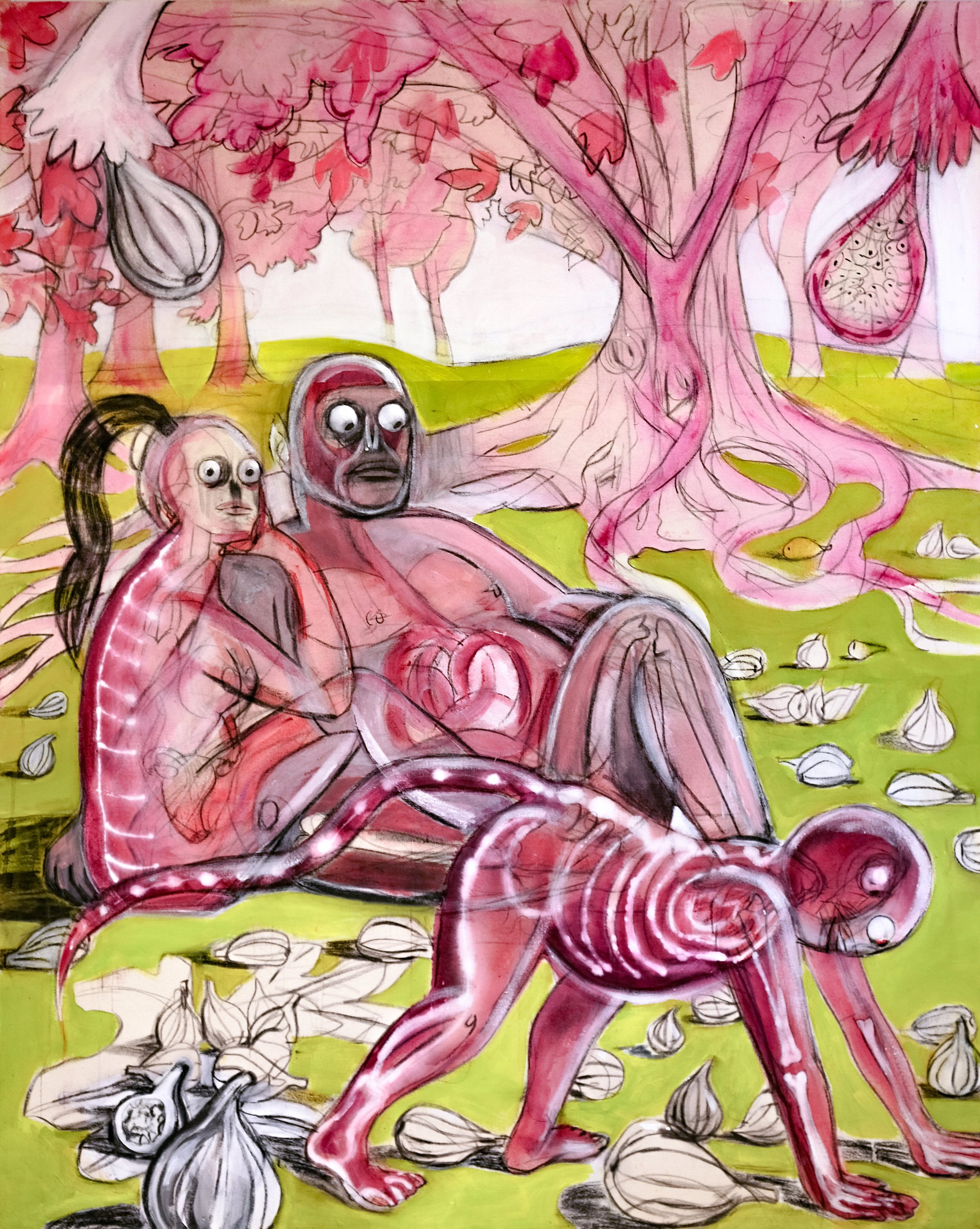

The Gothic, long considered dark and monstrous, was fascinated by naturalism, intrinsically symbolic and laden with meaning. In this collection of works, Ġulja Holland finds refuge in the opportunity to continue in this tradition of painting and art-making. Her work attempts to invert the biblical, inviting us to paradise not as a place of Genesis, but one of a distant future which we have yet to lead ourselves to. The halls of Spazju Kreattiv carry the visions that Holland has of this place, exposing a negotiation between peace, cataclysm, and anxiety about the defining parameters of our current time and an attempt at returning to a place where we see beyond solely a gaze which is human. This comes across not only in the subject matter but even more so in its tactility. The materiality of the show works to unveil and de-skin in order to convey and reconfigure the subjects she is studying.

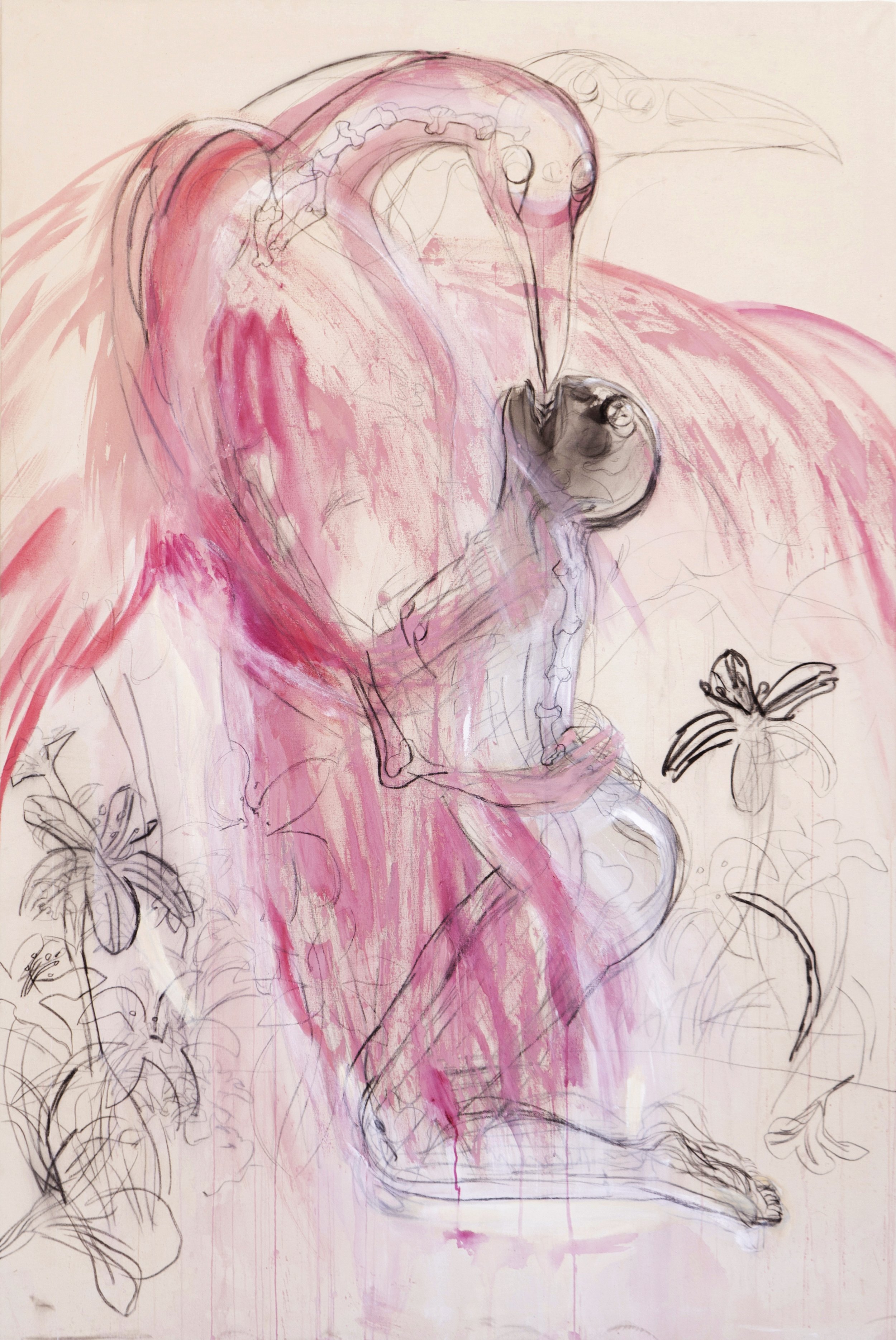

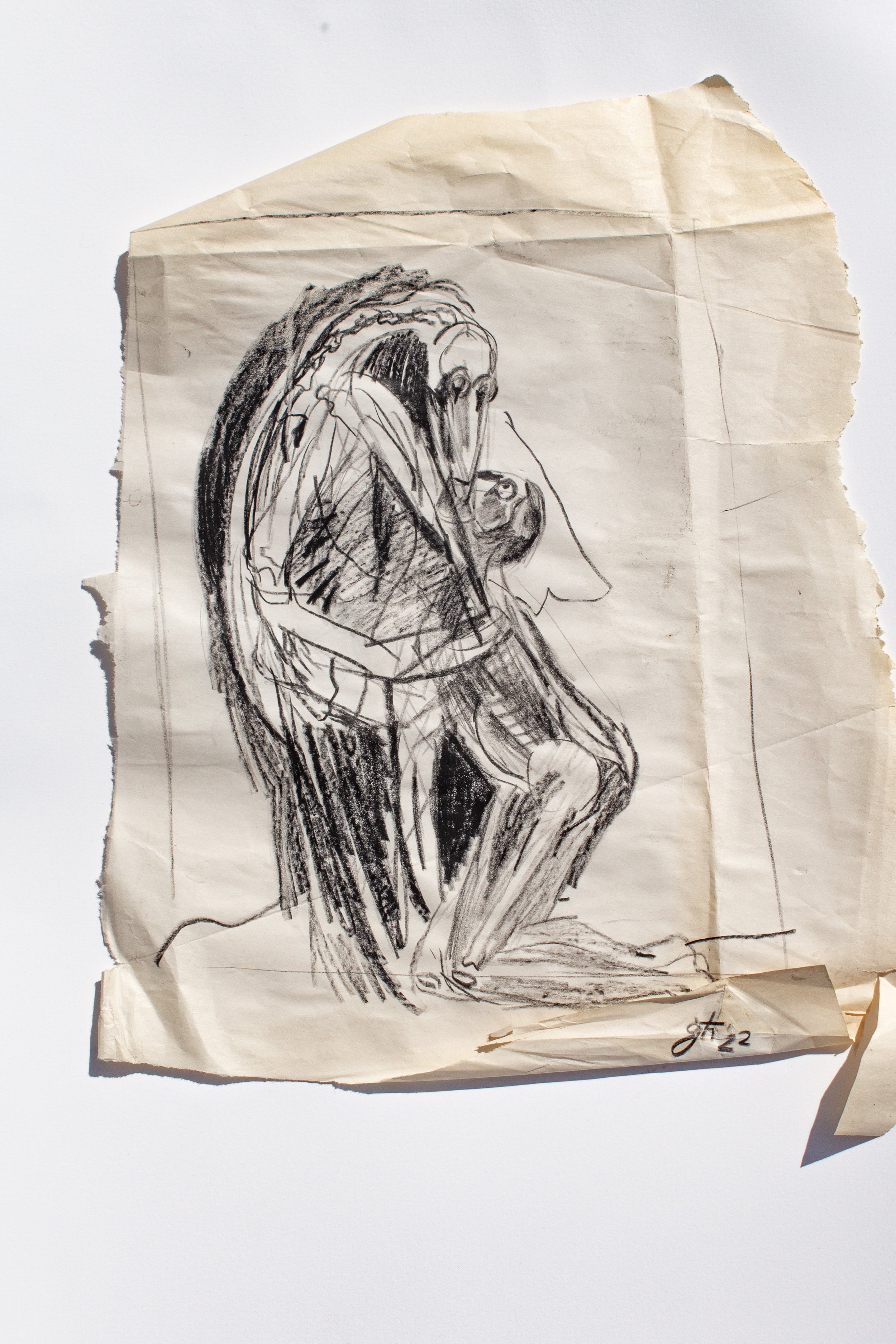

Holland’s method is on display in its totality. The pre-painting digital collages which she builds help the audience to see using prosthetic eyes, and we can observe her mind at work. Marks of pentimenti emerge repeatedly and quite prominently, revealing a reckoning with the subject and the fiction she is seeking to create around it. In works like ‘Full Bloom’ and ‘Le Petit Mort’, this is immediately present. As if the eagle-like bird in Bosch’s John of Patmos has grown into the monsters he writes about, in these paintings by Gulja Holland nature has taken over. Here, the human is at the creature’s mercy, in two passionate reworkings of Leda and the Swan. One can’t help but associate with images of hunting and animals in captivity, and the inversion that Holland is establishing with these works. This vision she is pushing for establishes a new authority and focus. In a world dominated by injustice and crisis in gender, climate and biodiversity, she seeks to speculate on a time when nature takes over once more.

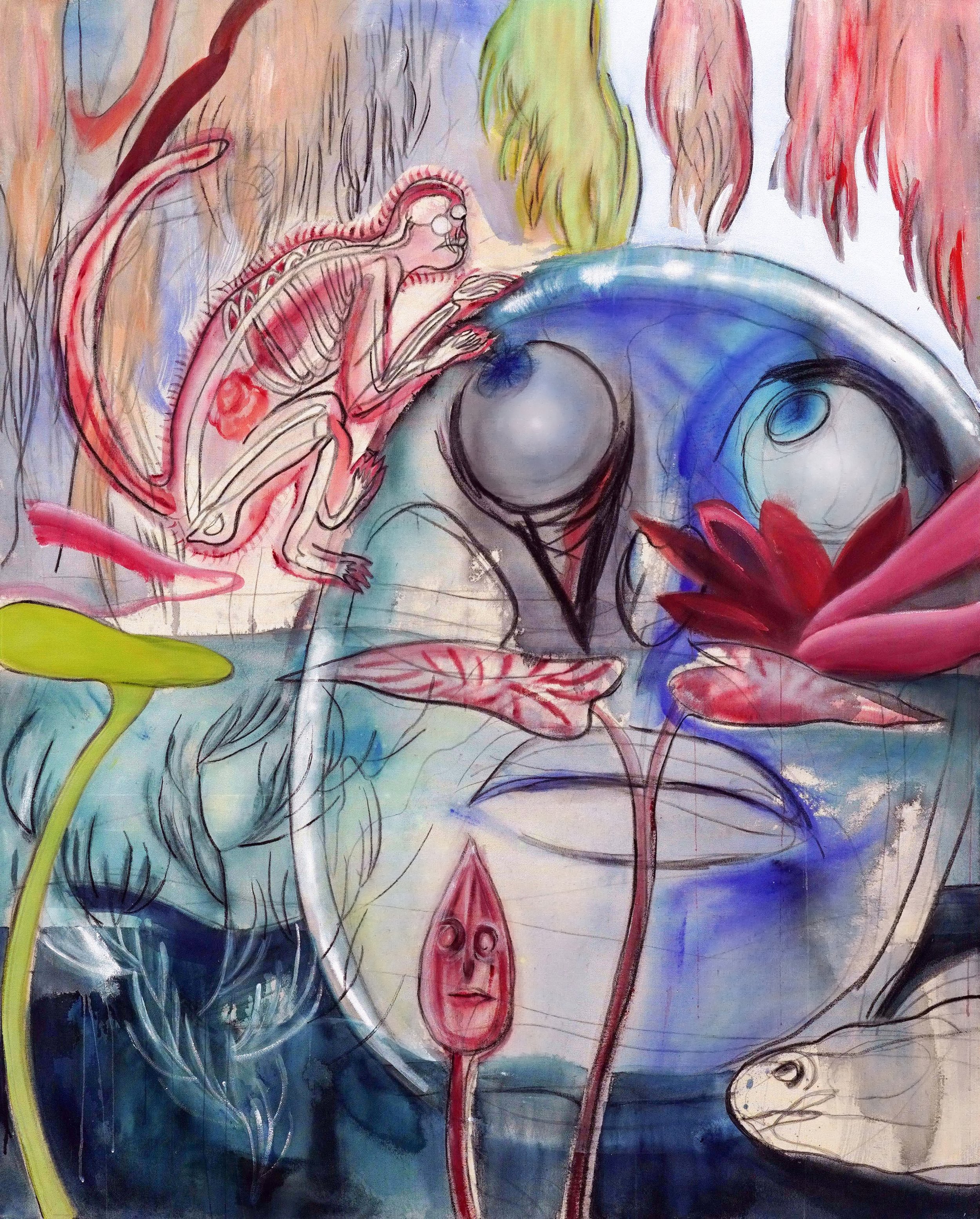

Beyond the liminal and gestural qualities of these two paintings, another important technical method which the show establishes comes in the form of the x-ray. The significance of relying on the x-ray for a piece’s inception lies in the equality Holland seeks to establish within nature. The x-ray challenges all ideas of hierarchy and power politics and reduces all beings to the fabric which allows them to navigate the world. In ‘Thirty’ we see the earliest development of this, which continues to persist in works like ‘Sophie’s Choice’, ‘The Watchers’ and ‘The Betrayal’. Holland speaks of the subliminal images that lie beyond the skin, and here perhaps she reaches the climax of what she seeks to do with this collection of works. Ġulja Holland is looking for potential alternatives to the bleak world she is expected to live and thrive in. She finds flowers in head scans and sees fruit in the results of a mammogram. The height of this comes in her depiction of ‘Eve’; a historically laden image of the first female which she chooses to present upon a largely black canvas. In this image, we see her most existentialist reckoning. The eyes are fixed upwards, and Holland seems to freeze her as the world spirals inwards.

Thirty, 2021

In this exhibition, Holland is showcasing her own innovations in paint-making after experiences in London, at PADA and in Malta. Her veiling and unveiling create a sense of the uncanny, as she toys between thick marks on canvas and thinner watercolour washes. The artist has developed a new means of assembling a painting, and this she does through digital and tactile techniques which we see her weave throughout the works.

The scope of this exhibition is to invite audiences in to see as Holland does. The Garden of Earthly Delights is a clear inspiration, not only because of its surreal and sinister subject but also because conceptually, it sets a location for alternative realities which contemplate the role of the human in the natural world. In these paintings, as in the work of Bosch, the human is but one character in a garden of creatures, animals and fruit, where things are constantly happening, and hierarchies are renegotiated constantly. The world of one painting can coincide with—but almost chooses to act independently of—the worlds of any other. Ġulja Holland’s practice is increasingly more fascinated by this position as a storyteller, and this is where the gothic surfaces as a strong tool. As Holland sets us up to enter a world of accelerated destruction, chaos and calamity, she seeks to provide ammunition for beauty, justice and a newfound harmony in another.

John’s Book of Revelations speaks of a beast which rises from the sea. Ġulja Holland’s most recent works showcase her enchantment by seals and her disdain for the image of their persecution at the hands of humans. In ‘Song of Sirens’ and ‘Seal’ the sea becomes a bloodbath, as she applies the same technique we have seen elsewhere in this show. Holland is borrowing from found imagery to raise a warning towards what we need to save ourselves from and what we can lead the world to. This reaches a climax in ‘A New Gothic’, the most monumental work she is presenting. There is a superimposition of the seals upon a distant figure. The white, painterly corals caress the composition, and both human and animalistic characters seem to co-exist, not unlike her ‘Mother and Child’, one of the first works created back in her time in London. Both paintings present a world of heightened serenity, and there is a prospective harmony she is achieving.

In this exhibition, Holland is frozen in a position not too dissimilar to that of the exiled John of Patmos in Bosch’s work. Her eyes are fixed in a trance, and creatures are around her waiting to become something else as her quill hits the canvas. Chaos and calamity offer lessons to jump in and out of, where the human race is laden with responsibility—however, the ultimate lesson lies in abandoning the anthropocentric gaze in favour of a greater empathy; for other creatures and the environment.

Holland’s paintings aim for an urgent rethinking of the power struggles within the natural world. In removing the clothes, furs, veils and skins from her subjects she manages to reveal what is common, rather than what segregates. The monstrous and barbaric, terms used to explain the gothic, are here stripped of their negative connotation, in favour of a shared, altogether alternative, and prosperous future.